By Meng Fei, Nelson Peng, and Peter Calthorpe

By Meng Fei, Nelson Peng, and Peter Calthorpe

**This article was originally published in Chinese by The Paper on March 24, 2016.**

From work, you would ride your bike to your child’s school to pick them up. With your kid settled on the back of the bike, you would catch up on his or her day at school before you arrive at the grocery store. After buying food, it would then not be long until you were at home preparing dinner. This was a common family scene in China. Twenty years later, goods are more plentiful, the economy is more developed, and technology has improved. But in many ways, life has become harder. You have to drive to get to work, and circle around the block many times to find parking at the grocery store. Then, picking up your child from school yields even more driving and parking hassles. There are many causes for this, but the most direct is that formerly mixed-use cities are getting split up. Urban planners call this single-use zoning.

In certain cases, single-use zoning still has its virtues and it can play a vital role for urban development. The main purpose is to separate incompatible uses, such as locating polluting industries far from residential areas. Single-use green belts can also provide environmental buffers and keep quality of life high. However, land development models and market trends have recently disrupted the location of compatible uses next to each other. What have emerged are sprawling residential areas that lack businesses and public service facilities, or office parks where you cannot even find a place to have breakfast. This problem is even more serious in the U.S. where cars dominate. The solution is to build mixed-use neighborhoods.

Mixed-use development integrates compatible land uses to create an environment that encourages biking and walking and allows people to easily access key amenities. In most big cities in China, rent is almost certainly higher for a property immediately surrounded by a school, hospital, shops, restaurants, and parks. Politicians, academics, professional organizations, and civil society have been pushing for mixed-use. Among them, one of the most successful efforts is calculating “Walk Scores.”

WalkScore – A new evaluation system for housing and neighborhood

WalkScore is a publicly-accessible website created in 2007 by three Americans (Matt Lerner, Mike Mathieu, Jesse Kocher) in Seattle. At the core of the website is an algorithm that generates a score from zero to 100 for any U.S address based on the number and layout of amenities and walkability.

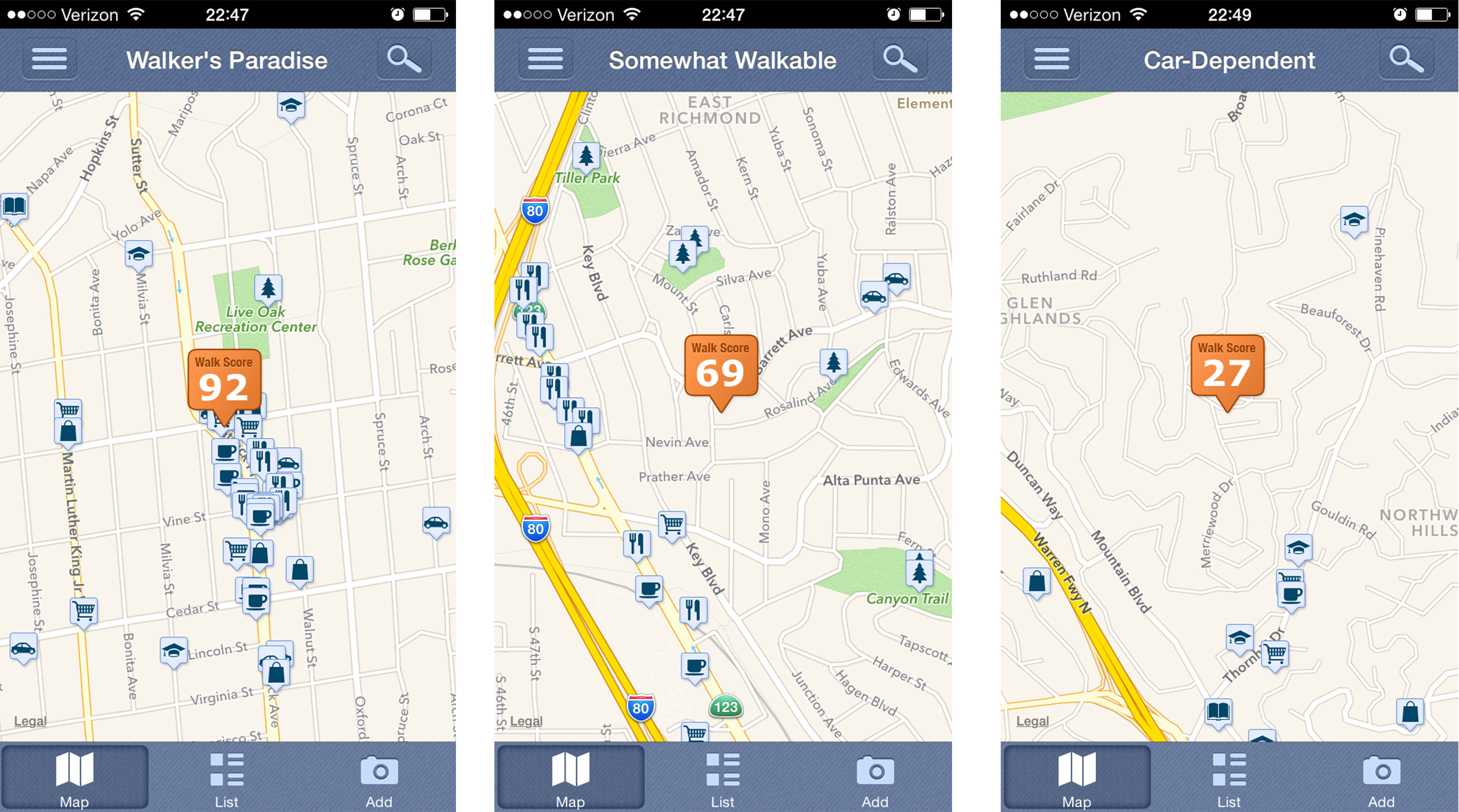

Users can easily get the WalkScore for any location from their website or cellphone app.

Users can easily get the WalkScore for any location from their website or cellphone app.

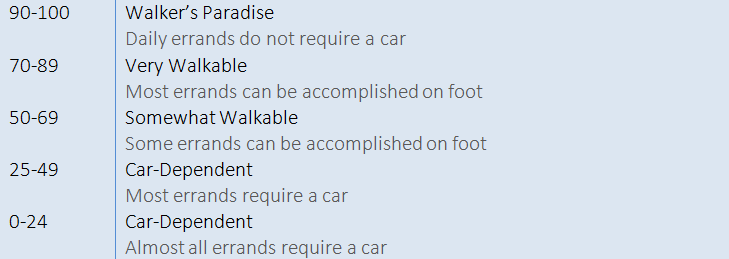

The WalkScore categorizes amenities into 11 types: restaurant & bar, café, grocery, park, schools, car share and bike rental, arts and community services, other shopping, recreation, health and errands (such as banks and post offices). Intersection density, block scale, and walking distance to amenities are all considered into the algorithm. The scores are further categorized into 5 types:

In the past few decades, walkability, mixed-use, human scale, and other elements of a healthy neighborhood have been accepted as mainstream in America. However, WalkScore is the first time these concepts have been quantified. Now, the public has an index to easily compare the convenience and accessibility of different neighborhoods, and with this comes far-reaching impacts. It has been widely adopted by many fields, especially in real estate. The consulting firm IMPRESA has studied 90,000 real estate transactions among 15 U.S metropolitan areas and found out the difference in housing value for each WalkScore point can be as high as $3,000. In the housing and rental markets, people are now asking “What’s the WalkScore?” instead of “What’s the price,” a topic that is less intrusive and represents a positive trend.

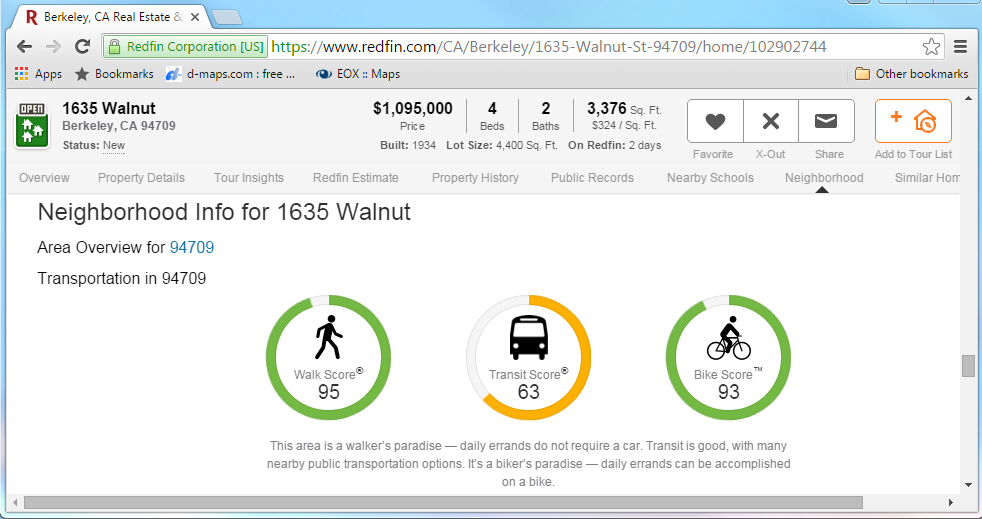

Popular real eastate websites, such as Redfin and ZipRealty, have incorporated WalkScore into their property selection information.

Popular real eastate websites, such as Redfin and ZipRealty, have incorporated WalkScore into their property selection information.

Enhancing mixed-use through detailed zoning – Experience from Jinan

The popularity of WalkScore in North America has signaled the market preference for compact and mixed-use development to governments and developers. This has been a bottom-up process. The situation is different in China. Firstly, the government owns all the land and has a strong guiding role in development. Secondly, China’s urbanization is occurring very rapidly, so wrong patterns often repeat themselves, making top-down government intervention necessary. Below, the case of Jinan shows how the government can use detailed regulatory plans to introduce mixed-use development.

With the Jinan West high-speed rail station in operation, the city is busy building the Jinan East High Speed Rail Station, the city’s second high-speed rail station. The new station will be a major impetus for development in surrounding areas, the Zhangma District (about 550 ha) being one of the first such projects. Calthorpe Associates has been invited to lead the District’s urban design, partnered with a local design institute that will provide regulatory and technological support. With the development of new districts, it can take a while to build up the atmosphere for commercial activity. Developers can be biased toward building residential, which can delay the commercial development.

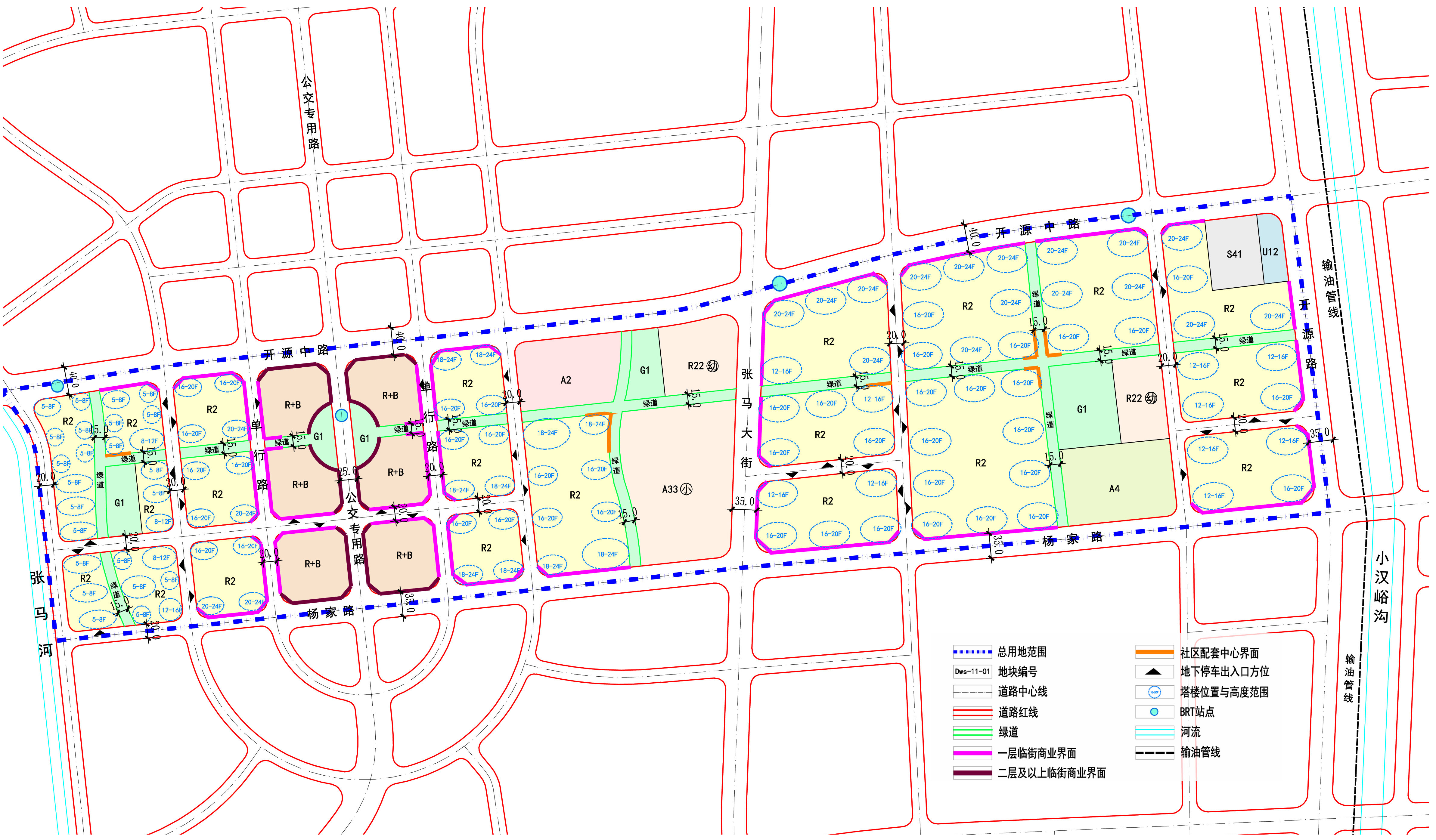

In Zhangma District’s plan, specific features include:

-

- Plan a dense green road network, and arrange neighborhood parks at the intersections to serve as community centers that provide public services (schools, elderly care centers, cultural centers, etc.). This way, all of the area’s residents (especially the elderly and children) can walk or bike to any public facilities, greatly enhancing the level of car-free accessibility.

Green road network and public amenities facilities (source: Calthorpe)

Green road network and public amenities facilities (source: Calthorpe)

-

- For large residential neighborhoods, the government usually requires that developers plan for a certain amount of commercial services. With this project in Jinan, if the land was given to a developer, all of the commercial space would be concentrated to one or two areas, making it difficult for many of the residents in the northern section to have walking access to the commercial space. To prevent this, we distribute the commercial spaces throughout the commercially zoned areas. This guarantees more even distribution of the commercial space and that residents can access the commercial areas by walking.

- Calthorpe Associates worked closely with the Jinan Planning Bureau to convert the technical details to a comprehensive compact development plan. They also obtained the Jinan Planning Department’s approval to turn the plan into a legal document and also include it in the land sale clauses, which guarantees full implementation of the design. In the regulatory plan, the “minimum street front floor area for businesses” was increased to ensure the even distribution of amenities and to optimize the locations of the street front businesses and community centers.

The Zhangma neighborhood compact zoning map shows an even distribution of public facilities and commercial amenities (source: Jinan Planning Institute #3).

The Zhangma neighborhood compact zoning map shows an even distribution of public facilities and commercial amenities (source: Jinan Planning Institute #3).

Challenges and suggestions for mixed-use strategy in China

Although mixed-use is gradually gaining acceptance in China, it still faces market, property management, and planning barriers.

First, the market: over the past two to three decades of rapid urbanization, a number of outstanding commercial real estate firms have emerged and matured, but most of them are housing developers. Compared to the quick and lucrative housing developments, commercial real estate, especially large developments, requires long-term management with a longer payback period. From the authors’ experience working on Chinese projects, developers in most cases will try to lower the ratio of public amenities and commercial elements to gain more land for residential development.

Second, urban planning policies have also made implementing mixed-use difficult. The Urban Land-Use and Planning Categorization Standard issued by MOHURD in 1991 was meant for statistical work related to urban planning. However, due to the lack of planning tools, this standard was widely applied in all types of planning activities nationwide. It rigidly separates land uses and provides little flexibility in the planning and management, while also lacking mechanisms to adapt to a changing market. For example, there is no categorization for residential towers with retail, which are commonly seen in most cities. The market is evolving, the internet is becoming more prominent, and mixed-use commercial development patterns will need to become even more sophisticated. Cities must catch up with these trends and establish the right tools and regulations to adapt.

These challenges incite a few suggestions for how mixed-use should be implemented:

- Use a simple and comparable index to advocate planning ideas. Although there are many approaches and methods to measure walkability, it is necessary to turn concepts such as livability or walkability into simple and usable metrics for people to understand and apply to their own lives.

- Design the walking network based on where public amenities and services are located. The purpose of mixed-use is to make peoples’ lives more convenient by shortening commutes and encouraging car-free travel. Hence, it is important to not just consider the availability of these amenities, but also their accessibility.

- The municipal government should take advantage of their administrative authority and seek a more active role and use detailed regulatory plans to promote mixed-use.

- The mixed-use strategy requires longer-term proper management. There should be more collaboration between different groups to streamline the process.

++++

About the authors:

Fei Meng – Fei is a Program Manager at the Institute of Transportation Studies at the University of California, Davis. She is an expert on low-carbon cities and sustainability, focusing on China’s urban situation. She is a results-oriented project developer with a successful record in national and international forums designing, launching, and implementing new projects and programs.

Nelson Peng – Peng is a Senior Designer at Calthorpe Analytics, focusing mainly on urban design in China. His projects include Chenggong New Town, Yuelai Eco-city, Xiamen West, Zhuhai Tangjiawan Bay, and the Jinan New East Station master plan. Peng received his Bachelor’s degre from Sun Yat-sen University and his Master’s degree from University of Pennsylvania.

Peter Calthorpe – Calthorpe is the founder of Calthorpe Associates and founding member and the first president of The Congress for New Urbanism. He has practiced urban planning and design globally for over 30 years and has many renowned publications in the field, including Urbanism in the Age of Climate Change, The Next American Metropolis, The Regional City, and TOD in China.